Macabre Beauty: Lam Qua’s Medical Portraits

Visual essay by Wenyu He rethinking the colonial project of Peter Parker’s medical mission in Canton over a century ago.

WENYU HE

Editor’s note

This visual essay by Wenyu He focuses on medical portraits by the Chinese treaty-port artist Lam Qua 林官 (Kwan Kiu Cheong 關喬昌, 1801–1860) for the American medical missionary Peter Parker (1804–1888), painted between 1834 and 1855. The paintings present us with bodily pathologies that Parker was meant to cure. They have been described in a seminal article by Ari Larissa Heinrich (1999) as a project to transmit an ideological message about the curability of the “Sick Man of Asia,” while simultaneously “creating and pathologizing a protoracial Chinese identity.” But do Lam’s portraits truly support Parker’s colonial project? Close visual analysis of the painted tumours and pathologies as artifacts of ugliness and beauty––a macabre beauty––reveals a different story. (8-12 minute read)

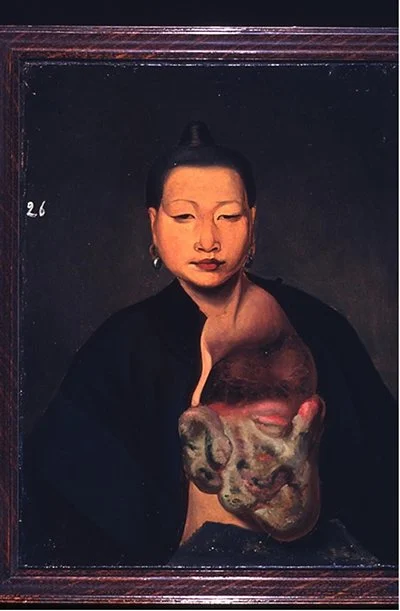

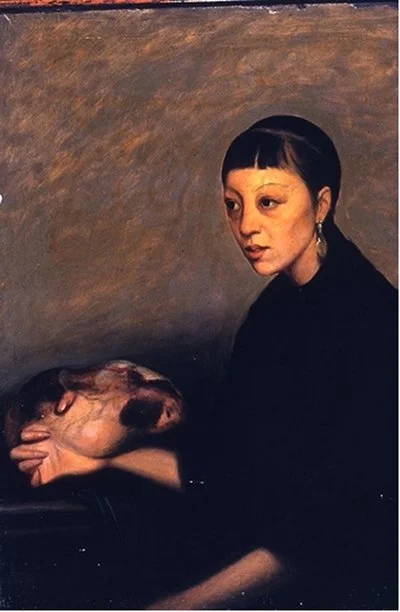

Lam Qua. Portrait No. 26, ca. 1834–1855. Courtesy of the Cushing/Whiting Medical Library, Yale University

The woman’s eyes are half-closed beneath carefully plucked brows. The light strikes her right cheekbone, illuminating an apple-like fullness, a sparkling earring, the edge of a lip. Her left temple and curve of the chin where the light does not reach is darkened and dimensional. Shadow is rendered by a light gray wash over immaculate brushstrokes, blended gently so that the marks of making are obscured. Her simple black robe hangs open. Below is a twisting tumourous form, its texture both dry and wet, fossilized and also softly thick with pale grey-greens, shocking pinks, lavender. The artist’s hand appears in gestural strokes.

This painting is one in a series of more than ninety portraits by the commercial painter Lam Qua 林官 (Kwan Kiu Cheong 關喬昌, 1801–1860) for the American medical missionary Peter Parker (1804–1888), painted in the years between 1834 and 1855 (see images below). They were commissioned by Parker to support his fund-raising efforts in the States. The portraits are described in a seminal article by scholar of Chinese literature Ari Larissa Heinrich as “paintings of gross pathologies...(that) confront us with a stark, undeniable dimensionality...suggest[ing] that they...are a ‘real’ record of real illnesses: straightforward likenesses of objectively definable pathologies (tumours, growths) that happen to share the frame with sensitive portrayals of their human hosts” (1999, 241–242). Heinrich’s concern is with the ways that the painter “uses composition and content to transmit a message about the ‘curability’ of Chinese culture, simultaneously creating and pathologizing a protoracial Chinese identity, all in keeping with the propagandistic requirements of Parker’s missionary ideology” (1999, 242).

Lam Qua’s medical portraits, which contain numerous depictions of grotesque, fearsome, and deformed bodies, can safely be categorized as ugly when they arouse violent repulsion, horror, and disgust among viewers. If such deformity is woven into a racialized narrative to embody a Chinese identity as the “Sick Man of the East” in need of Western technologies of medicine in order to survive, it is indeed a point where we should pause and think about what that means politically and ideologically, as Heinrich argues. However, Umberto Eco’s On Ugliness (2007) prompts a different set of questions. Eco raises the issue of how to see ugliness as a parallel concept to beauty, which is most commonly associated with the purpose of creating art.

This visual essay asks after the complexities of seeing ugliness as macabre beauty in the portraits, and on the artist’s terms. Why make the ugly so aesthetic? When ugliness is so ostensibly the theme for which the exaggerated tumours stand as testaments, why does Lam Qua intervene in the pictorial space in an aesthetic pursuit? Put slightly differently: Why beautify irreversible ugliness? What is the point?

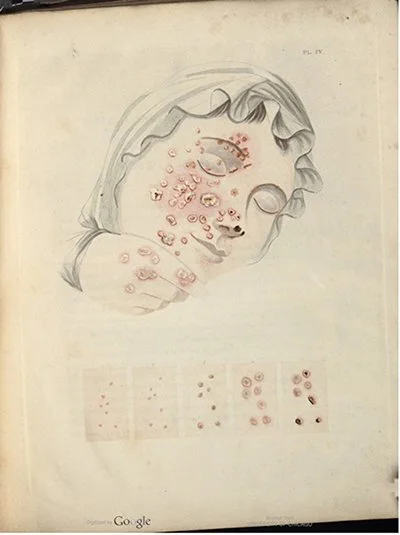

We might first consider that there is an aesthetics to depictions of illness around the time that Lam Qua took up the brush. Take, for instance, Lam’s contemporary Dr. John D. Fischer’s Description of the Distinct, Confluent, and Inoculated Small Pox, Varioloid Disease, Cox Pox, and Chicken Pox (1836), which contains illustrations of faces marred by smallpox and, similar to Lam’s art, embodies a visible painterly intervention in depicting distorted human figures. The woman’s eyes are closed with a tranquil smile on her face, and she is wearing a nightcap, indicating she may be dozing. The shadows on her face and nightcap are a soft light gray, the pathological redness on her face is rendered lightly in watercolour, and the nightcap is shaded with lines, adding more texture to the cottony fabric and to the portrait itself. The hand under her chin—it may or may not be hers but is also affected by pox—seems to pull her face toward the imagined viewers, and the right half of her face is covered by inflamed points and papulæ.

John D. Fischer. Description of the Distinct, Confluent, and Inoculated Small Pox, Varioloid Disease, Cox Pox, and Chicken Pox, 1836. Boston, Printed by Dutton and Wentworth, p5, #25.

According to the medical account to which the image is attached, the image is most likely delineating the period of eruption when smallpox spreads over the face and extends into the body (Fischer 1836, 10). That the visual center of the portrait is the red and festering papulæ, evoking the synesthesia of discomfort, itchiness, and ache, contrasts with the serenity of the woman’s facial expression in a jarring way. Here we can see how the painter chooses to heighten the softness of the lady’s visage and, rather than rendering it as purely medical or functional, tries to make the portrait, despite its pathological distortion, somewhat pleasurable to look at.

The most significant similarity with Lam’s portraits is the stoic expression of the figures. What it seems to demonstrate is a formulaic approach to the depiction of disease in North America (where Fischer worked) and in Hong Kong, or perhaps, a shared aesthetic. Yet the most significant difference between Fischer and Lam is that the two artists represent disease in distinct ways: one pinpoints the exact shape and distribution of papulæ, leaving nothing to the imagination, while the other leaves the represented tumour blurry and indistinguishable with unclear boundaries, escaping the viewer’s clear purview of vision.

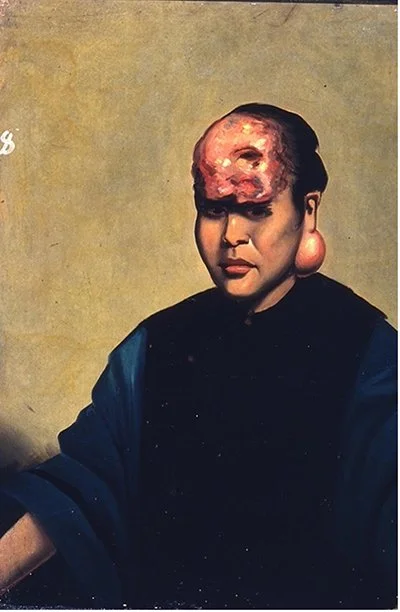

Another of Lam Qua’s portraits depicts a woman with a huge tumour on her forehead and a smaller one hanging on her earlobe (Figure 6). The woman sits against a khaki-coloured wall, and a front light brightens up her visage. The shadows on her face, as per Lam Qua’s usual stylistic choice in almost all his medical portraits, are very dark, reminiscent of European Baroque arts. The contrast between the light and dark areas makes the figure more defined, even adding a sense of theatricality through the eyes hidden in the shadow created by the tumour on her forehead, giving a subtle dynamic to the still moment. As always, the artist pays attention to the balance of warm and cool colours in the portrait. The dark blue garment contrasts with the yellow background and face, and the absolute center of the picture is defined by the smallest but most striking red.

Lam Qua. Portrait No. 08, ca. 1834–1855. Courtesy of the Cushing/Whiting Medical Library, Yale University

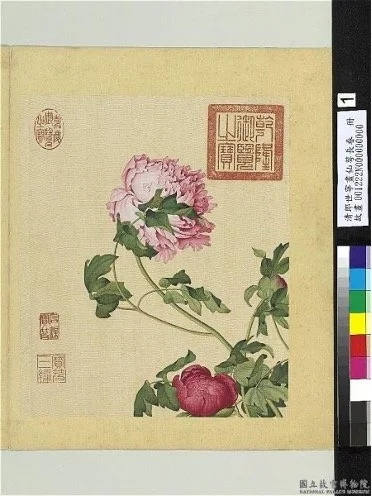

The tumour on the forehead is the most visible painterly intervention, and it demonstrates an aesthetic purpose resisting the conventional perception of clear-cut ugliness versus beauty. The tumour is roughly a round shape resembling a peony flower, for which a peony painting by the Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766) made at the Qing court in Beijing can serve as a point of reference. Castiglione’s peony is also loosely circular in shape. It is red and white, with the deep red outlining the shadowed parts and the white making tangible the lighter petals.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining 郎世寧), Xian’e changchun ce mudan清郎世寧畫仙萼長春冊牡丹 [Immortal Calyxes, Eternal Spring]. National Palace Museum, Taipei

The tumour on the woman’s forehead has a more complex texture and colour variation. Looking closer, we may see a colour scheme that can even be called playful: Small patches of bright yellow dot the red, enlivening the lighted center, and grayish blue and green blocks around the edges reduce the overly warm tones. Some orange is subtly mixed into the surface around the small, seemingly bottomless blackhole in the middle of the tumour, with an orange square pointing right into the hole that is layered like petals of a flower at its opening. Highly saturated red is at the lower part of the tumour, and underneath it is dark shadow with sharp edges, indicating hard light. It is a grotesque tumour carefully and finely crafted.

Simply put, the colours on the tumour can be seen as unrealistic. The brush strokes that create small patches of yellow, white, and orange are visible and seem deliberate, diminishing the realistic sense of the tumour itself, while making the tumour vibrant and pleasing to the eye, almost like depicting a flower (even if at the same time the tumour signifies deformity, illness, and the pathologized body).

The other tumour located on the woman’s left ear resembles a giant, pink pearl earring on a compositional level while also echoing the colours of the forehead. Without the “pearl,” the huge tumour on the forehead would make the head look too heavy, but the heavy earlobe balances the weight. Its surface texture is smooth and hard against the soft and silky “peony.” It also contrasts with the larger tumour’s centric indentation by being almost perfectly semi-oval and conforming to the curves of the woman’s neck. The two malignant growths make the picture come alive, which, given their nature, is almost counterintuitive.

For the rest of the image is simple in colour and laconic in contour. The woman is wearing a black top that has dark blue sleeves with faint sheen on the fabric surface. The clothing is not as finely limned, and considering the overall chiaroscuro, it plays the role of dimming the darker part and setting off the light side, with light attenuation done at the bottom to make the bright areas stand out even more. We can also readily tell from the colour structure and the lighting that tumours are unquestionably the most central aesthetic objects of painterly endeavours, and they are also the very things that the artist wants viewers to pause and look at.

One last thing about this woman with a peony and a pearl tumour is her subtle smile. Her expression is reserved, her eyes hidden in the shadow cast by the tumour on her forehead. There is unhealthy deep red at the bottom of those eyes, adding a secretive and disturbing air. For some reason unknown to viewers, she is wearing a smile so faint that it is almost invisible: if we cover her mouth, the smile completely disappears. She seems a mystery by not revealing anything about herself—usually we can assess identity from the jewelry or the headpiece, but tumours replace those elements. Therefore, all we have is a woman with two beautiful, or at least two artistic, tumours sitting quietly, harboring an enigmatic smile, as if hiding something.

Asking after the aesthetics of ugliness leads to a slightly different question: Are these paintings beautiful? Kant argues in Critique of Judgment that aesthetic judgment reveals itself first in sensation and independent of consciousness of the intentional activity (1987, 63). If we take his words seriously, on a sensational level, Lam Qua’s medical portraits evoke a strong sense of displeasure precisely because viewers are asked to partake in experiencing the tumours growing on human bodies. Thus, the paintings are not beautiful. But if we leave the pure nature of tumours aside and only observe the way they are depicted as we have done thus far––if we only look––observing the carefully planned compositions, decorative surfaces of tumours, lighting, and colour choices, there is indeed a feeling of bizarre pleasure which grows out of looking at something not supposed to be beautiful and yet is strangely compelling and aesthetically intriguing.

Lam Qua. Portrait No. 06, ca. 1834–1855. Courtesy of the Cushing/Whiting Medical Library, Yale University

A painting of a huge tumour on a woman’s hand attests further to a special Lam Qua aesthetic, which embodies such a macabre beauty. The woman seems to be conversing with an interlocutor outside the frame, with a tranquil smile on her face. Her right hand, laid gently on the table, has an enormous tumour on it that completely alters the shape of the hand—the thumb grows directly on the tumour and from a spot against the normal anatomical sense of a human hand. The tumour itself is almost monstrous, for it resembles a fetus crouching in a membrane. The fetus, so to speak, seems to have a small visage and several organs, and it is parasitic on this woman’s right hand, while she is oblivious to its existence, as if she is used to living calmly with what looks like a monster’s egg. Unlike the peony tumour that works as embellishment, the hand tumour, rather than just an aestheticization of the grotesque, invites viewers to peep into it, which contains unspeakable, surreal gray-and-yellow parts that go beyond the boundary of what we usually consider as the human body.

It is jarring how the hand tumour functions almost as a handbag or a cushion where the hand rests. Its monstrosity actually makes the whole picture come alive. Within the membrane, there seems to be mucus soaking up some chunks, and a tinge of unrealistic bright pink and green further enlivens the tumour. In a way, the tumour seems like a living being.

If we cover the hand tumour, the portrait will seem rather dull. The dullness arises from the black robe, the texture of which cannot be seen, and the woman’s hair, which is the same colour as her robe, so the hair and the robe blend together to accent her yellowish-toned face. The colour of this portrait is somewhat plain if we compare the painting with the previous one. What is the most arresting is simply the tumour, an unnamable entity that is at once parasitic and consuming the woman’s flesh by eating up her hand.

Is this painting beautiful? The pleasure of looking comes from the imagination inspired by the eldritch tumour, which in its exaggeration achieves an artistic purpose rather than just being dryly scientific and straightforward.

So, we return to our original question: Why beautify ugliness? The paintings, embodying both ugly disease and macabre beauty, disrupt the formula of representing deformed bodies in a medical sense, thereby defying any clear-cut interpretation of their purposes. The viewer’s eye cannot see, exactly, what it is looking at; the tumours dissolve into an artful play of oil and colour and through their compositional placement and heighten attention to their abstract yet vital beauty.

Sensitivity to the portraits––and even more, to the ways we see them––goes far in demonstrating that Lam Qua did not “use composition and content” to “transmit a ‘real’ record of real illnesses.” The colonial agenda that the paintings are accused of is, to a large extent, discursive rather than directly evident in the paintings themselves. In other words, like Peter Parker, we could call the portraits documents of the “Sick Man of Asia,” but the portraits, by being artistic, imaginative, and beautiful in a jarring way, visually diminish and even resist the colonial propaganda that they are supposed to perform.

Works Cited

Eco, Umberto. 2007. On Ugliness. Translated by Alastair McEwen. London: Harvill Secker.

Fisher, John D. 1836. Description of the Distinct, Confluent, and Inoculated Small Pox, Varioloid Disease, Cow Pox, and Chicken Pox. 2nd ed. Printed by Dutton and Wentworth.

Heinrich, Larissa. 1999. “Handmaids to the Gospel: Lam Qua’s Medical Portraiture.” In Tokens of Exchange: The Problem of Translation in Global Circulations, edited by Lydia H. Liu, 239–275. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. [1790] 1987. Critique of Judgment. Translated by Werner S. Pluhar. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.

Wenyu He is a doctoral student in Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Michigan. Her research centers on Chinese Ming-Qing literature and gender. She is interested in the gender ecology manifested in late imperial writing and the historical milieu that enabled such writing to flourish.

Email address: wenyuhe@umich.edu